Project Mercury

| McDonnell Mercury spacecraft | ||

|---|---|---|

The Mercury spacecraft with escape tower |

||

| Description | ||

| Role: | Suborbital and orbital spaceflight | |

| Crew: | one pilot | |

| Dimensions | ||

| Height: | 11.5 ft | 3.51 m |

| Diameter: | 6.2 ft | 1.89 m |

| Volume: | 60 ft³ | 1.7 m³ |

| Weights (MA-6) | ||

| Launch: | 4,265 lb | 1,935 kg |

| Orbit: | 2,986 lb | 1,354 kg |

| Post Retro: | 2,815 lb | 1,277 kg |

| Reentry: | 2,698 lb | 1,224 kg |

| Landing: | 2,421 lb | 1,098 kg |

| Rocket engines | ||

| Retros (solid fuel) x 3: | 1,000 lbf ea | 4.5 kN |

| Posigrade (solid fuel) x 3: | 400 lbf ea | 1.8 kN |

| RCS high (H2O2) x 6: | 25 lbf ea | 108 N |

| RCS low (H2O2) x 6: | 12 lbf ea | 49 N |

| Performance | ||

| Endurance: | 34 hours | 22 orbits |

| Apogee: | 175 miles | 282 km |

| Perigee: | 100 miles | 160 km |

| Retro delta v: | 300 mph | 483 km/h |

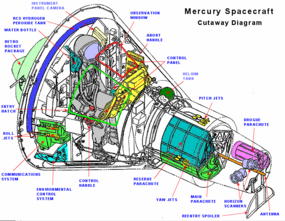

| Mercury spacecraft diagram | ||

Mercury spacecraft cutaway |

||

| McDonnell Mercury spacecraft | ||

Project Mercury was the first human spaceflight program of the United States. It ran from 1959 through 1963 with the goal of putting a human in orbit around the Earth. The Mercury-Atlas 6 flight on February 20, 1962, was the first Mercury flight to achieve this goal.[1] The program included 20 unmanned launches followed by six flights with astronaut pilots. Early planning and research was carried out by the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics,[2] and the program was officially conducted by the newly created NASA.

The project name came from Mercury, a Roman mythological god who is often seen as a symbol of speed. Mercury is also the name of the innermost planet of the solar system, which moves faster than any other and hence provides an image of speed, although Project Mercury had no other connection to that planet.

The Mercury program cost approximately $384 million,[3] the equivalent of about $2.9 billion in 2010 dollars.

Contents |

Goals and Guidelines

The goals of the program were to orbit a manned spacecraft around Earth, investigate man's ability to function in space and to recover both man and spacecraft safely.[4] NASA also established program guidelines: existing technology and off-the-shelf equipment should be used wherever practical, the simplest and most reliable approach to system design would be followed, an existing launch vehicle would be employed to place the spacecraft into orbit, and use of a progressive and logical test program. Project requirements for the spacecraft were that it must be fitted with a reliable launch-escape system to separate the spacecraft and its crew from the launch vehicle in case of impending failure, the pilot must be given the capability of manually controlling spacecraft attitude, the spacecraft must carry a retrorocket system capable of reliably providing the necessary impulse to bring the spacecraft out of orbit, a zero-lift body utilizing drag braking would be used for reentry, and that the spacecraft design must satisfy the requirements for a water landing.[5]

Research and development

On October 7, 1958, T. Keith Glennan, the first Administrator of NASA, approved the Mercury project.[6] On December 17 Glennan announced Project Mercury publicly.[7]

On December 29, 1958 North American Aviation was awarded a contract to design and build Little Joe boosters for test flights.[8] In January 1959 McDonnell Aircraft Corporation was chosen to be prime contractor for the Mercury spacecraft, and the contract for 12 spacecraft was awarded in February. In April seven astronauts, known as the Mercury Seven or more formally as Astronaut Group 1, were selected to participate in the Mercury program.

In May 1959 North American Aviation delivered the first two Little Joe boosters, and in June the Big Joe booster was delivered. In July the planned use of Jupiter boosters in the Mercury program was canceled in favor of Atlas flights.[9] In October General Electric delivered to McDonnell the ablative heat shield designated for installation on the first Mercury spacecraft. In December the launch vehicle for Mercury-Redstone 1 was ready to begin static tests installed on a test stand at ABMA.

In January 1960 NASA awarded Western Electric Company a contract for the Mercury tracking network. The value of the contract was over $33 million.[10] Also in January, McDonnell delivered the first production-type Mercury spacecraft, less than a year after award of the formal contract. On February 12, Christopher C. Kraft, Jr. was appointed to head the Mercury operations coordination group.[11] Kraft was asked to, "come up with a basic mission plan. You know, the bottom-line stuff on how we fly a man from a launch pad into space and back again. It would be good if you kept him alive." In April, the first spacecraft was delivered to Wallops Island for the beach-abort test. The test was completed successfully on May 9.[12]

Spacecraft

Because of their small size, it was said that the Mercury spacecraft were worn, not ridden. With 1.7 m³ of habitable volume, the spacecraft was just large enough for the single crew member. Inside were 120 controls: 55 electrical switches, 30 fuses and 35 mechanical levers.[13] The spacecraft was designed by Max Faget and NASA's Space Task Group.[14][15]:26-28

Despite the astronauts' test pilot experience NASA at first envisioned them as "minor participants" during their flights, causing many conflicts between the astronauts and engineers during the spacecraft's design. Nonetheless, contrary to other reports, the project's leaders always intended for pilots to be able to control their spacecraft, as they valued humans' ability to contribute to missions' success.[15]:23-25 John Glenn's manual attitude adjustments during the first orbital flight was an example of the value of such control.[15]:33 The astronauts requested—and received—a larger window and manual reentry controls.[15]:24-25

During the launch phase of the mission, the Mercury spacecraft and astronaut were protected from launch vehicle failures by the Launch Escape System. The LES consisted of a solid fuel, 52,000 lbf (231 kN) thrust rocket mounted on a tower above the spacecraft.[15]:28 In the event of a launch abort, the LES would fire for 1 second, pulling the Mercury spacecraft and the astronaut away from a defective launch vehicle. The spacecraft would then descend on its parachute recovery system. After booster engine cutoff (BECO), the LES was no longer needed and was separated from the spacecraft by a solid fuel, 800 lbf (3.6 kN) thrust jettison rocket that fired for 1.5 seconds.

To separate the Mercury spacecraft from the launch vehicle, the spacecraft fired three small solid-fuel, 400 lbf (1.8 kN) thrust rockets for 1 second. These rockets were called the posigrade rockets.[15]:28

The spacecraft was only equipped with attitude control thrusters; after orbit insertion and before retrofire they could not change their orbit. There were three sets of high and low powered automatic control jets and separate manual jets, one for each axis (yaw, pitch, and roll), and supplied from two separate fuel tanks, one automatic and one manual. The pilot could use any one of the three thruster systems and fuel them from either of the two fuel tanks to provide spacecraft attitude control. The Mercury spacecraft were designed to be completely controllable from the ground in the event that something impaired the pilot's ability to function.

The spacecraft had three solid-fuel, 1000 lbf (4.5 kN) thrust retrorockets that fired for 10 seconds each.[15]:28 One was sufficient to return the spacecraft to Earth if the other two failed. The firing sequence (known as ripple firing) required firing the first retro, followed by the second retro five seconds later (while the first was still firing). Five seconds after that, the third retro fired (while the second retro was still firing).

There was a small metal flap at the nose of the spacecraft called the "spoiler". If the spacecraft started to reenter nose first (another stable reentry attitude for the spacecraft), airflow over the "spoiler" would flip the spacecraft around to the proper, heatshield-first reentry attitude, a technique called 'Shuttlecocking'. During reentry, the astronaut would experience about 8 g-forces on an orbital mission, and 11-12 g's on a suborbital mission.

Initial designs for the spacecraft suggested the use of either beryllium heat-sink heat shields or an ablative shield. Extensive testing settled the issue - ablative shields proved to be reliable (so much so that the initial shield thickness was safely reduced, allowing a lower total spacecraft weight), and were easier to produce (at that time, beryllium was only produced in sufficient quantities by a single company in the US) and cheaper.

NASA ordered 20 production spacecraft, numbered 1 through 20, from McDonnell Aircraft Company, St. Louis, Missouri. Five of the twenty spacecraft, #10, 12, 15, 17, and 19, were not flown.[16] Spacecraft #3 and #4 were destroyed during unmanned test flights.[16] Spacecraft #11 sank[16] and was recovered from the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean after 38 years.[17] Some spacecraft were modified after initial production (refurbished after launch abort, modified for longer missions, etc.) and received a letter designation after their number, examples 2B, 15B. Some spacecraft were modified twice; for example, spacecraft 15 became 15A and then 15B.[18]

A number of Mercury Boilerplate spacecraft (including mockup/prototype/replica spacecrafts, made from non-flight materials or lacking production spacecraft systems and/or hardware) were also made by NASA and McDonnell Aircraft.[19][20] They were designed and used to test spacecraft recovery systems, and escape tower and rocket motors. Formal tests were done on test pad at Langley and at Wallops Island using the Little Joe and Big Joe Atlas rockets.[21]

Boosters

The Mercury program used three boosters:[15]:28-30

- Little Joe - 8 suborbital robotic flights, 2 carrying monkeys. Launch escape system tests.

- Redstone - 4 suborbital robotic flights, 1 carrying a chimpanzee; 2 piloted suborbital flights.

- Atlas - 4 suborbital robotic flights; 2 orbital robotic flights, 1 carrying a chimpanzee; 4 piloted orbital flights.

Little Joe and a Mercury Boilerplate[22] was used to test the escape tower and abort procedures.[23] Redstone was used for suborbital flights, and Atlas for orbital ones. Starting in October, 1958, Jupiter missiles were also considered as suborbital launch vehicles for the Mercury program, but were cut from the program in July 1959 due to budget constraints. The Atlas boosters required extra strengthening[24] in order to handle the increased weight of the Mercury spacecraft beyond that of the nuclear warheads they were designed to carry. Little Joe was a solid-propellant booster designed specially for the Mercury program. The Titan missile was also considered for use for later Mercury missions;[25] however, the Mercury program was terminated before these missions were flown. The Titan was used for the Gemini program which followed Mercury.

The Mercury program used a Scout booster for a single flight, Mercury-Scout 1, which launched a small satellite intended to evaluate the worldwide Mercury Tracking Network. The rocket was destroyed by the Range Safety Officer after 44 seconds of flight.[26]

Unmanned flights

The program included 20 robotic launches. Not all of these were intended to reach space and not all were successful in completing their objectives. Four of these flights included non-human primates, starting with the fifth flight (1959) which launched a Rhesus macaque named Sam[27] (after the Air Force's School of Aerospace Medicine). The Mercury program's complete roster of non-human space-farers is given below:

- Sam, a Rhesus macaque, launched 4 December 1959 on Little Joe 2 to 85 km altitude.

- Miss Sam, a Rhesus macaque, launched 21 January 1960 on Little Joe 1B to 15 km altitude.

- Ham, a chimpanzee, launched 31 January 1961 on Mercury-Redstone 2 for a suborbital flight.

- Enos, a chimpanzee, launched 29 November 1961 on Mercury-Atlas 5 for a 2-orbit flight.

| Mission | Rocket | Call Sign | Launch Date | Launch Time | Duration | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury-Jupiter | Jupiter | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Cancelled in July, 1959 - Proposed suborbital launch vehicle for Mercury. Not flown. |

| Little Joe 1 | Little Joe | LJ-1 | 21 August 1959 | N/A | 00d 00h 00 m 20s | Test of launch escape system during flight. |

| Big Joe 1 | Atlas 10-D | Big Joe 1 | 9 September 1959 | N/A | 00d 00h 13 m | Test of heat shield and Atlas / spacecraft interface. |

| Little Joe 6 | Little Joe | LJ-6 | 4 October 1959 | N/A | 00d 00h 05 m 10s | Test of spacecraft aerodynamics and integrity. |

| Little Joe 1A | Little Joe | LJ-1A | 4 November 1959 | N/A | 00d 00h 08 m 11s | Test of launch escape system during flight. |

| Little Joe 2 | Little Joe | LJ-2 | 4 December 1959 | N/A | 00d 00h 11 m 06s | Carried Sam the monkey to 85 kilometres in altitude. |

| Little Joe 1B | Little Joe | LJ-1B | 21 January 1960 | N/A | 00d 00h 08 m 35s | Carried Miss Sam the monkey to 9.3 statute miles (15 kilometres) in altitude. |

| Beach Abort | Launch escape system | Beach Abort | 9 May 1960 | N/A | 00d 00h 01 m 31s | Test of the Off-The-Pad abort system. |

| Mercury-Atlas 1 | Atlas | MA-1 | 29 July 1960 | 13:13 UTC | 00d 00h 03 m 18s | First flight of Mercury spacecraft and Atlas Booster. |

| Little Joe 5 | Little Joe | LJ-5 | 8 November 1960 | N/A | 00d 00h 02 m 22s | First flight of a production Mercury spacecraft. |

| Mercury-Redstone 1 | Redstone | MR-1 | 21 November 1960 | N/A | 00d 00h 00 m 02s | Launched 4 inches (100 mm). Settled back on pad due to electrical malfunction. |

| Mercury-Redstone 1A | Redstone | MR-1A | 19 December 1960 | N/A | 00d 00h 15 m 45s | First flight of Mercury spacecraft and Redstone booster. |

| Mercury-Redstone 2 | Redstone | MR-2 | 31 January 1961 | 16:55 UTC | 00d 00h 16 m 39s | Carried Ham the Chimpanzee on suborbital flight. |

| Mercury-Atlas 2 | Atlas | MA-2 | 21 February 1961 | 14:10 UTC | 00d 00h 17 m 56s | Test of Mercury spacecraft and Atlas Booster. |

| Little Joe 5A | Little Joe | LJ-5A | 18 March 1961 | N/A | 00d 00h 23 m 48s | Test of the launch escape system during the most severe conditions of a launch. |

| Mercury-Redstone BD | Redstone | MR-BD | 24 March 1961 | 17:30 UTC | 00d 00h 8 m 23s | Redstone Booster Development - test flight. |

| Mercury-Atlas 3 | Atlas | MA-3 | 25 April 1961 | 16:15 UTC | 00d 00h 07 m 19s | Test of Mercury spacecraft and Atlas Booster. |

| Little Joe 5B | Little Joe | AB-1 | 28 April 1961 | N/A | 00d 00h 05 m 25s | Test of the launch escape system during the most severe conditions of a launch. |

| Mercury-Atlas 4 | Atlas | MA-4 | 13 September 1961 | 14:09 UTC | 00d 01h 49 m 20s | Test of Mercury spacecraft and Atlas Booster. Completed 1 orbit. |

| Mercury-Scout 1 | Scout | MS-1 | 1 November 1961 | 15:32 UTC | 00d 00h 00 m 44s | Test of Mercury tracking network. |

| Mercury-Atlas 5 | Atlas | MA-5 | 29 November 1961 | 15:08 UTC | 00d 03h 20 m 59s | Carried Enos the Chimpanzee on a two orbit flight. |

Manned flights

Astronauts

The first Americans to venture into space were drawn from a group of 110 military pilots[28] chosen for their flight test experience and because they met certain physical requirements. NASA announced the selection of seven of these - known as the Mercury Seven - as astronauts on 9 April 1959,[29] though only six of the seven flew Mercury missions, after Slayton was grounded due to a heart condition.

- Malcolm Scott Carpenter, USN (born 1925)

- Leroy Gordon "Gordo" Cooper, Jr., USAF (1927–2004)

- John Herschel Glenn, Jr., USMC (born 1921) First American to orbit the Earth.

- Virgil Ivan "Gus" Grissom, USAF (1926–1967) Died during Apollo 1 Pre-Launch Test

- Walter Marty "Wally" Schirra, Jr., USN (1923–2007)

- Alan Bartlett Shepard, Jr., USN (1923–1998) First American in space

- Donald Kent "Deke" Slayton, USAF (1924–1993) Grounded in 1962 due to irregular heartbeat, reinstated in 1972 and later flew on the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in 1975.[30]

Beginning with Alan Shepard's Freedom 7 flight, the astronauts named their own spacecraft, and all added "7" to the name to acknowledge the teamwork of their fellow astronauts.

Piloted Mercury launches

| Mission | Callsign | Rocket | Designation | Pilot | Launch Date | Launch Time | Duration | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury-Redstone 3 | Freedom 7 | Redstone | MR-3 | Shepard | 5 May 1961 | 14:34 UTC | 00d 00h 15 m 28s |

First American to make a suborbital flight into space. |

| Mercury-Redstone 4 | Liberty Bell 7 | Redstone | MR-4 | Grissom | 21 July 1961 | 12:20 UTC | 00d 00h 15 m 37s |

Second suborbital flight. Spacecraft sank before recovery when hatch unexpectedly blew off, recovered 1999. |

| Mercury-Atlas 6 | Friendship 7 | Atlas | MA-6 | Glenn | 20 February 1962 | 14:47 UTC | 00d 04h 55 m 23s |

First American to orbit the Earth (for a total of 3 orbits). Spacecraft's retropack retained during re-entry due to concerns about heatshield. |

| Mercury-Atlas 7 | Aurora 7 | Atlas | MA-7 | Carpenter | 24 May 1962 | 12:45 UTC | 00d 04h 56 m 15s |

3 orbits. Reentered off-target by 402 km. Pilot Carpenter replaced Deke Slayton. |

| Mercury-Atlas 8 | Sigma 7 | Atlas | MA-8 | Schirra | 3 October 1962 | 12:15 UTC | 00d 09h 13 m 11s |

Carried out engineering tests. 6 orbits. |

| Mercury-Atlas 9 | Faith 7 | Atlas | MA-9 | Cooper | 15 May 1963 | 13:04 UTC | 01d 10h 19 m 49s |

First American in space for over a day. Last American to orbit the Earth solo. 22 orbits. |

| Mercury-Atlas 10 | Freedom 7-II | Atlas | MA-10 | Shepard | N/A | N/A | N/A | Intended to be a 3-day mission in October 1963. Cancelled 13 June 1963. |

| Mercury-Atlas 11 | Atlas | MA-11 | Grissom | N/A | N/A | N/A | Intended to be a 1-day mission in 1963. Cancelled by October 1962. | |

| Mercury-Atlas 12 | Atlas | MA-12 | Schirra | N/A | N/A | N/A | Intended to be a 1-day mission in 1963. Cancelled by October 1962. |

Mercury flight insignias

Flight patches that purport to be patches from various Mercury missions are available to the public. In reality, these patches were designed by private entrepreneurs long after the Mercury program ended. When genuine flight patches were created by crews in the Gemini program, this caused a public demand for Mercury flight patches, which was filled by these private entrepreneurs. The only patches the Mercury astronauts wore were the NASA logo and a name tag. Each manned Mercury spacecraft, however, was decorated with a flight insignia. These are the genuine Mercury flight insignias.

Project Mercury stamp

In 1962 the US Post Office honored the first orbital flight of a U.S. astronaut with the Project Mercury Commemorative stamp. This was the first U.S. postal issue to depict a manned spacecraft. The stamp first went on sale in Cape Canaveral, Florida on February 20, 1962, the same day as the Project Mercury launch putting the first U.S. astronaut into orbit.

See also

|

|

References

- ↑ "Mercury-Atlas 6 (23)". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/mercury/missions/friendship7.html.

- ↑ "Major Events Leading to Project Mercury". NASA. http://history.nasa.gov/SP-4001/p1a.htm.

- ↑ "The history of NASA's Mercury Program". Helium.com. http://www.helium.com/items/1429240-the-mercury-space-program.

- ↑ "Project Mercury". NASA Public Affairs Office. http://www-pao.ksc.nasa.gov/history/mercury/mercury-goals.htm.

- ↑ "Mercury Goals and Guidelines". NASA Public Affairs Office. http://www-pao.ksc.nasa.gov/history/mercury/mercury-overview.htm.

- ↑ Prepared by James M. Grimwood. "Research and Development Phase of Project Mercury". NASA MSC. http://history.nasa.gov/SP-4001/p2a.htm.

- ↑ "Project Mercury". U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission. http://www.centennialofflight.gov/essay/SPACEFLIGHT/Mercury/SP17.htm.

- ↑ "Little Joe Launch Vehicle". Boeing. http://www.boeing.com/history/bna/little_joe.html.

- ↑ "Mercury-Jupiter 2 (MJ-2)". Encyclopedia Astronautica. http://www.astronautix.com/flights/merr2mj2.htm.

- ↑ "Chronology - Quarter 1 1960". Encyclopedia Astronautica. http://www.astronautix.com/chrono/19601.htm.

- ↑ "Christopher C Kraft, Jr American Manager. Born 1924.". Encyclopedia Astronautica. http://www.astronautix.com/astros/kraft.htm.

- ↑ "PART II (B), Research and Development Phase of Project Mercury, January 1960 through May 5, 1961". NASA. http://history.nasa.gov/SP-4001/p2b.htm.

- ↑ "Project Mercury". U.S Centennial of flight commission. http://www.centennialofflight.gov/essay/SPACEFLIGHT/Mercury/SP17.htm.

- ↑ "Biographical Data, Dr. Maxime A. Faget". NASA. http://history.nasa.gov/Apollo204/faget.html.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 Logsdon, John M. with Roger D. Launius (editors) Exploring the Unknown: Selected Documents in the History of the U.S. Civil Space Program / Volume VII Human Spaceflight: Projects Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo The NASA History Series, 2008.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 "APPENDIX 6 - LOCATION OF MERCURY SPACECRAFT, AND EXHIBIT SCHEDULE". NASA. http://history.nasa.gov/SP-4001/app6.htm.

- ↑ "Liberty Bell 7 capsule raised from ocean floor". CNN. http://www.cnn.com/TECH/space/9907/20/grissom.capsule.01/.

- ↑ "Mercury MA-10". Encyclopedia Astronautica. http://www.astronautix.com/flights/meryma10.htm.

- ↑ "Boilerplate Mercury Capsule". NASA. http://grin.hq.nasa.gov/ABSTRACTS/GPN-2000-003008.html.

- ↑ "Mercury". Encyclopedia Astronautica. http://www.astronautix.com/project/mercury.htm.

- ↑ NASA Mercury History Sections #44 and #47

- ↑ A Fieldguide to American Spacecraft

- ↑ Mercury Boilerplate Tests

- ↑ "MA-2: Trussed Atlas Qualifies the Capsule". NASA. http://history.nasa.gov/SP-4201/ch10-4.htm.

- ↑ "More Than a Spacecraft". NASA. http://history.nasa.gov/SP-4203/ch3-2.htm.

- ↑ "Mercury Scout 1". NASA. http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraftDisplay.do?id=MERCS1.

- ↑ "Sam the Monkey After His Ride in the Little Joe 2 Spacecraft". NASA. http://grin.hq.nasa.gov/ABSTRACTS/GPN-2002-000042.html.

- ↑ "Alan B. Shepard, Jr.". NASA. http://history.nasa.gov/40thmerc7/shepard.htm.

- ↑ "The 40th Anniversary of the Mercury Seven". NASA. http://history.nasa.gov/40thmerc7/intro.htm.

- ↑ "APOLLO-SOYUZ". NASA. http://history.nasa.gov/apollo/apsoyhist.html.

Further reading

|

|

External links

- The Mercury Project (Kennedy Space Center)

- Project Mercury A Chronology (Prepared by James M. Grimwood)

- Space Medicine In Project Mercury By Mae Mills Link

- Project Mercury Drawings and Technical Diagrams

- Project Mercury Simulator for Mac and PC

- The Mercury Redstone Project (PDF) December 1964

- Project Mercury familiarization manual (PDF) November 1961

- Various PDFs of historical Mercury documents including familiarization manuals.

- NASA History Series Publications (many of which are on-line)

- U.S. Spaceflight History- Mercury Program

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||